Sunday, November 18, 2018

'Black Boy' by Richard Wright

Black Boy was an instant best-seller when it was published in 1945, and has remained one of the best-selling books by the pioneering African-American writer, Richard Wright, who lived from 1908 until 1960. It is classed as an autobiography but it reads more like a novel. Wright was already famous as a writer of stories and essays, and his first novel, Native Son, had been an immediate best seller when it was published in 1941.

Notably, the version of Black Boy that became the best-seller is not the book we read today. Wright composed the book in two parts. Part One, called "Southern Night," covers his youth in the South, and Part Two, called "The Horror and the Glory" and only half as long, covers his young adulthood in Chicago. Wright's major point is that life in the South did not prepare him for life in the North; he had to go through a second childhood to learn the ways of the city.

The two parts are very different. The first part strives for mythic status; Richard presents himself as a stand-in for every poor black boy in the South who wanted to be respected as an individual. The second part is increasingly specific to his own life and loses its mythic status, as Richard tries to understand and justify his actions in Chicago. Because of this, his publisher persuaded him to release the first part on its own in 1945. This is justifiable on the grounds that it is a coherent and complete work of art, but for Richard it meant that his story was brutally truncated. In the 1990s, Wright's original work was published whole as he had intended, and that is the version people read nowadays.

The book's full title is Black Boy (American Hunger), and in it Wright depicts spiritual and emotional hunger as well as the constant physical hunger of his youth. One of his major points is that racial discrimination deprives African-Americans of opportunities for self-realization and self-respect. He asserts that racism limits the emotional and cultural development of black people, so they have no idea of their own worth. Fortunately there has been enough progress toward equality that Wright's depiction of racism in the South in the first half of the 20th century seems dated now, but in its time, it was incendiary because it was shocking to see a secret aspect of American society depicted so vividly.

Racism is not the book's only subject. The boy Richard was permanently scarred by a peculiarly nightmarish childhood that deprived him of any form of worth. He defined the problem as one of racial discrimination, but I think his warped family situation made him dwell on this issue.

As a child, Richard is almost completely deprived of love and support. His closest relationship is with his mother, who routinely slaps him for asking too many questions or bringing up forbidden subjects. After she suffers a series of paralyzing strokes, the best she can do is to nag him weakly to do his best in school. As she becomes more helpless, he loses his sense of connection with her. Richard's father abandons the family when Richard is 6, leaving them in abject poverty. His mother's family takes them in, but they treat Richard like a little heathen.

The most excruciating part of his situation concerns religion. Richard's grandparents and an aunt who lives with them are ardent 7th-Day Adventists who insist on a host of forbidding rules and are determined that Richard join their sect. As a boy who had experienced little in life beyond hunger and disrespect, Richard can't accept any religious belief. Long passages are devoted to the Adventists' efforts to recruit him, and the thoughts he has about spiritual beliefs as a child. In fact, one of his earliest experiences of self-realization is his unwillingness to accept their beliefs, and his inability to pretend that he does in order to fit in. This condemns him to total rejection by his mother's family. After his mother converts to Methodism, she too tries to save his soul, and resorts to emotional pressure to get him to be baptized, but he soon returns to bitter skepticism.

Richard's family sees him as a wayward boy whose actions are always bad, and you can see their point. At the age of 4, he burns the house down. Soon after, he kills a kitten. At age 6, he becomes an alcoholic. He learns to talk dirty before he learns to read. He taunts the Jewish store owner with the same kind of prejudice he is subjected to. He is paralyzed by shyness in school. He unwittingly sells racist tracts. He refuses to be punished for things he didn't do, and uses a knife or straight razors to protect himself from his abusive relatives. When he graduates from 8th grade, he insists on giving the Valedictorian speech that he wrote himself rather than the one the principal wrote for him. As he grows older, he wants to read novels and write stories, the work of the devil in his families' view. He wants to work on Saturdays, a holy day for the Adventists. After he gets old enough to work full time, he finds he will never be able to save enough money to escape North, so he resorts to participating in a scam for extra money, and finally engages in theft to get a stake. Wright presents all these incidents in novelistic detail, including his thoughts and feelings at the time.

His extreme poverty forced Richard to seek work at a very young age, and this is when he begins to encounter racial prejudice. Wright catalogs every sort of racial indignity that a boy could experience in the heart of the South, and he analyzes just how these experiences affected his development. White people expect black people to be totally and smilingly subservient, like slaves. No matter how hard Richard tries to conform, he seems uppity to the whites, who frequently bully him into leaving his job.

Wright's childhood was so deprived— emotionally, spiritually, and economically—that his pursuit of knowledge and self-realization seems miraculous, totally inexplicable. He becomes an ardent reader despite the disapproval of his family and the scarcity of reading materials. His formal education is patchy due to poverty, but he is passionate about seeking knowledge, and adventure as well, through reading. Where did he get that passion? Where did he get the massive intelligence to digest all that material? Wright shows very few positive influences on his life.

Not surprisingly, Wright's adult life in Chicago is considerably more complicated than his childhood in the South. No longer can he encapsulate his experience into a string of deftly drawn episodes; various aspects of his life overlap and intersect, and learning takes place over longer arcs. On the plus side, there is less public racial discrimination; he can sit anywhere on public transportation, and he doesn't have to defer to white folks. But racial prejudices remain at a deeper level. This is true for Richard as well, who notices that even when white people try to treat him respectfully, he still assumes they are the same as white people in the South. His personality is so hardened that it is hard for him to form relationships.

Career-wise, Wright does rather well, though he never acknowledges this. He starts out as an errand boy and dishwasher, but he soon passes the exam for postal clerk. Meanwhile he reads all the important novels of his day and tons of sociology and psychology. During the Depression he becomes an agent for insurance and burial societies, discouraging work that nevertheless gives him access to the lives of a wide variety of poor black people. When that job dries up, a relief organization assigns him to be an orderly in a medical research institute. Finally he gets a job with the South Side Boys' Club that he finds deeply engrossing. Later he is assigned to do publicity for the Federal Negro Theater, which is a writing job, at least; when that fails, he is assigned to do publicity for a white experimental theatrical company.

What really muddies his narrative is his relationship with the Communist party. Richard finally meets some people with similar social and philosophical views, and through them he gets drawn into the John Reed Club, a group of artists and writers which was associated with the Communist party. At first the theory of Communism, and its version of history, enthrall Wright, but he realizes the idealistic Communist activists are deeply ignorant of the life of ordinary black people. He is suspicious of them, but he is drawn in when they offer to publish some of his stories. From this point, his memoir becomes a messy recital of political manipulation, group rivalries, and Communist tactics as he is unexpectedly propelled into a leadership position in Chicago's Communist party and just as unexpectedly demoted and reviled, as the international party becomes more rigid. After two chapters of ups and downs in the party, his relationship is finally ended definitively, and he concludes the book in a state of deep disillusionment, though nevertheless determined to continue writing.

In addition to racism, Wright struggles with rampant anti-intellectualism. His ardent and wide-ranging self-education plays a painfully ambivalent role in his life. On the positive side, reading is his only escape from his frustrating life; on the other, it automatically makes him unusual and suspect, not only among his family, but also his friends. As an adult, he talks like a person with a college education. This is an advantage in building his career, but it makes him suspect among other Negro members of the Communist party, who are mostly unlettered new arrivals to the North, because it identifies him with their white oppressors.

The first time I read this book, I was disdainful of the long passages of explanation and analysis, considering them to be artless. But the second time, the composition sounded seamless, and I realized that the development of the author's understanding of life is an important part of the story. Wright desperately wanted to understand himself and to make himself understood, and his voice rings with probing sincerity in every word. Many critics believe Wright helped change racial relationships in America.

Thursday, September 27, 2018

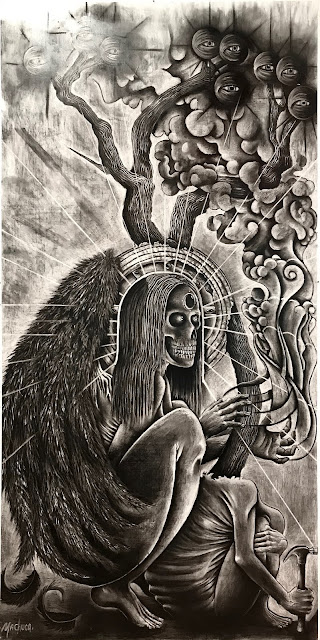

Miguel Machuca: Drawing Light from Darkness

Miguel Machuca is a local artist. Although he was born in Guadalajara, he came to this country with his family at the age of 10. Now around 40, he has been an established artist in San Jose for several years, as well as working in programs for autistic and at-risk youth.

He is currently having a show at the Triton Museum in Santa Clara called "Drawing Light from Darkness." It lasts until October 21, 2018. Check it out.

|

| Human Nature, 2014 |

Machuca's work comes from a spiritual point of view. It combines universal and personal symbols to express the unity of life. Here we see animal organs, leaves, an embracing horn, a penetrating eye, and a brick wall that transforms into a universal web—all heading toward the infinite.

|

| Fire within You, 2015 |

Machuca has developed a unique technique for applying charcoal to a white painted panel. He draws each form in silhouette, then uses an electrical eraser to model the silhouette by exposing the white underpainting as highlights. He literally draws the light out of darkness. Likewise, meditation—here represented by positions of the hands—reveals an individual's inner light.

|

| Sister Whisper, 2016 |

|

| Sister Deception, 2016 |

Sister Whisper and Sister Deception are a pair of imaginary figures representing choices. Sister Whisper enchains her pathetic follower with dreams of death. Sister Deception inspires the wretch to take action and start building. Together, they are called Orchestrated Religion, Part 2.

|

| Orchestrated Religion, Part 1, 2016 |

Orchestrated Religion, Part 1 rises above the dichotomy presented by the two Sisters. It asserts strength, confidence and wholeness, with a combination of symbols both familiar and strange.

|

| Manifest Your Destiny, 2016 |

Machuca uses his impressive draughtsmanship to render visions and symbols as though they were real. Here we have vision and power in the eyes and hands, with destiny represented by constellations, a wheel, and an embracing horn.

|

| 7th Sense, 2018 |

|

| Embrace Reality, 2018 |

This painful and frightening image has to do with accepting the need to work on one's self, as with the spike, in order to make an impact on the world, as with the hammer. The draughtsmanship is very skillful and evocative.

|

| Human Body Evolving Rose, 2018 |

Starting at the bottom, we see the mystical number 3, a key, a strong triangle that firmly supports ribs and organs, a rose, a wheel that evolves into a halo, two symmetrical roses, and on top, a happy parrot. This is about the stages of development in the journey toward beauty and truth.

|

| Full Consciousness in the Divine, 2018 |

All these artworks have many more symbols and interpretations than I have indicated. Because of their multilayered symbolism and their evocative draughtsmanship, these works stand on their own, without any biographical back story. However, once you read the Artist's Statement, also mounted on the gallery wall, the works take on an even larger significance.

- "This work is about my journey, before and after my experience with cancer. In January 2015, I was diagnosed with stage 4 Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma cancer, and with only a small percentage of survival. Although, this was not the spark for this show, I started on my body of work from a spiritual point of view and while I was working with the Triton Museum towards a solo exhibition, cancer made its appearance in my life, and I was hospitalized. Everything stopped until I was either better or dead. Through the days, I worked on a collection of ideas, drawings and sketches that could describe the internal bliss of a perpetual cycle of fear and doubt. My art saved my life. I caught myself in and out of a state of consciousness."

Machuca felt that having the goal of creating his first solo museum show gave him the motivation to generate personal strength to overcome cancer. The Triton Museum, and in particular its Deputy Director Preston Metcalf, deserves applause for recognizing Machuca's talent early in his career, and for encouraging him during his treatment and recovery. It's a great story.

To October 21

Tuesday, August 21, 2018

The Pre-Raphaelites of Victorian England

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was a secret society of rebellious young artists and writers that was formed in England in 1848 for the purpose of redefining British art. It disbanded within a few years, but the aesthetic principles expressed in its manifesto, and the works of the original members, affected three generations of English artists, who were generally known as Pre-Raphaelites. You may never have heard of this movement, or any of the artists in it, because the French dominated art history in the 19th century and formed our ideas of what makes good art. This movement precedes Impressionism, which came along twenty years later. In the mid-19th century, French painters like Corot, Courbet, and Manet, were into realism, which involved looking at real scenes of modern life. The Pre-Raphaelites, by contrast, were looking backward toward the type of painting that came before the Renaissance, which was literary, decorative, and symbolic.

When the founders of the PRB—William Holman Hunt (age 21), Dante Gabriel Rossetti (age 20), and John Everett Millais (age 19), and several of their friends—were studying at the art academy, the Renaissance was considered the peak of art history, and Raphael was the ultimate artist. The art that preceded it, the art of the Middle Ages, was considered 'primitive,' and given scant attention by their professors.

The members of the PRB felt that English art had stagnated because artists were mindlessly working in a Renaissance style, without rethinking it or adding anything new. They scornfully branded these artists 'Raphaelites,' and that is how they came to think of themselves as Pre-Raphaelites. However, this name is misleading because as the artists matured, they took an interest in the art of the late Renaissance, and even began to study the Venetians, who were on a different track completely.

The thing that bothered them most about the paintings of their teachers is that the edges of their forms and figures tended to merge with the background, leaving certain details unaccounted for. What they liked about the art of Northern Europe was that the edges of the forms are crisp and all the details are depicted distinctly, no matter how far away. This was their idea of 'truth to nature.'

The special exhibit currently at the Legion of Honor Museum of Art, called 'Truth and Beauty,' has only one example of the style they were rebelling against, this very nice self-portrait by Raphael from the Uffizi Museum in Florence.

One of the chief pleasures of the exhibit is the many examples of the art that inspired the Pre-Raphaelites.

One of the artists with a strong influence on the Renaissance was Domenico Ghirlandaio, a contemporary of Botticelli. Many artists got their training in his studio, including Michelangelo.

Piero di Cosimo was admired by the Pre-Raphaelites for his carefully articulated, naturalistic details.

Ironically, as the so-called Pre-Raphaelites matured, they became interested in the artists of the late Renaissance, and even the Venetians, whose robust and sensual figures, dynamic compositions, and deep shadows are a far cry from the work of Piero di Cosimo, or even Botticelli.

William Holman Hunt was a versatile artist who pursued various aspects of Pre-Raphaelite aesthetics over the course of a long career.

Late in his career, Hunt returned to the founding principles of the PRB in this depiction of a lyrical ballad by an English poet of the previous generation, Alfred, Lord Tennyson, one of the most popular poets of his time. It tells the story of a young noble woman who lives in a tower near Camelot, of the Arthurian legends, but she is prevented by a curse from looking at Camelot. She can view it only indirectly, through a mirror, and is further condemned to weave an image of what she sees. Here her frenzied and obsessive weaving is evoked by the thread wildly entangling her in her own work. This painting seems cluttered, confusing, and old-fashioned to the modern eye, but it has some wonderful effects. The spray of hair, activated not by the wind but by her furious work, is a beautiful pattern, and creates a mysterious, backlit cloud across the top of the image. The contrast between the dark shadows in the foreground and the brightly colored background (the scene in the mirror is more vivid in the painting than my photo), is striking and innovative. Hunt combined several unique jewel-tones and a variety of symbolism to depict the scene in sumptuous detail. This painting is considered the grand culmination of the Pre-Raphaelite agenda.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti came from a literary family. His father was a Dante scholar, his sister Christina became a famous poet, and his brother William Michael was a member of the PRB who became an influential art critic. Dante Rossetti also established himself in the history of English poetry, but he chose painting as his profession because he thought it would make more money. He became quite successful as a painter, made a lot of money, and continued to write poetry as a pastime. Sometimes he wrote a poem to accompany a painting; sometimes he painted a picture to illustrate a poem.

Although Rossetti painted a variety of literary and medieval subjects, he had a complicated love life, and he became increasingly obsessed with painting a certain ideal type of woman—voluptuous but melancholy, dreamy and decadent. He used a variety of models as his muses, but he gave them all a similar look and attitude. Each of these women is supposed to represent a character in a certain literary work, but that's just an excuse; you don't really need to know the story to get the point.

William Morris was a textile designer who was closely associated with Edward Burne-Jones and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. In 1861, these three artists and several others formed a decorative arts firm, which eventually became known as Morris & Co. This company manufactured and sold the tapestries designed by Burne-Jones. Below are two examples of tapestries designed by Morris himself. You may recognize these bold, repetitive patterns. This company still sells coveted wallpapers and fabrics.

Marie Spartali Stillman first became known for her stunning good looks. She was the daughter of a wealthy Greek merchant based in London, and her Grecian features gave her an exotic look to the pale British; in addition, she was over six feet tall. She was well-known among the Pre-Raphaelites, who vied to use her as a model. But after her marriage to an American journalist, she became one of the most prolific and successful artists of the movement, though she lived in both Europe and the U.S. and raised six children.

Kate Bunce was not directly connected with the Pre-Raphaelite set, which was mostly based in London. She was born and educated in Birmingham, an industrial town about halfway between London and Liverpool that had its own art academy, and even its own style. Although she did exhibit in London and all over England, as well as Birmingham, and had a successful career, she didn't achieve as wide recognition as the Londoners did. Also the Pre-Raphelite style seemed increasingly quaint in 20th century.

Conclusion

The Pre-Raphaelite school was essentially reactionary. They objected not only to conventional British painting but to modern life in general. They dreamed of an imaginary time when beauty reined supreme. But all those lonely ladies languishing in luxurious environments seem really irrelevant and quaint from the 21st century. The Pre-Raphaelites created some romantic effects in their work and it's fun to imagine the medieval world of knights and religion, but you can see why the French dominated art history in the 19th century. The French were looking outside the studio toward the real world, trying to capture the modern look, studying the effect of light and the nature of vision, and they embraced modernity, eagerly painting the newly built urban squares, railways, and bridges.

When the founders of the PRB—William Holman Hunt (age 21), Dante Gabriel Rossetti (age 20), and John Everett Millais (age 19), and several of their friends—were studying at the art academy, the Renaissance was considered the peak of art history, and Raphael was the ultimate artist. The art that preceded it, the art of the Middle Ages, was considered 'primitive,' and given scant attention by their professors.

The members of the PRB felt that English art had stagnated because artists were mindlessly working in a Renaissance style, without rethinking it or adding anything new. They scornfully branded these artists 'Raphaelites,' and that is how they came to think of themselves as Pre-Raphaelites. However, this name is misleading because as the artists matured, they took an interest in the art of the late Renaissance, and even began to study the Venetians, who were on a different track completely.

The thing that bothered them most about the paintings of their teachers is that the edges of their forms and figures tended to merge with the background, leaving certain details unaccounted for. What they liked about the art of Northern Europe was that the edges of the forms are crisp and all the details are depicted distinctly, no matter how far away. This was their idea of 'truth to nature.'

The special exhibit currently at the Legion of Honor Museum of Art, called 'Truth and Beauty,' has only one example of the style they were rebelling against, this very nice self-portrait by Raphael from the Uffizi Museum in Florence.

|

| Raphael, Self-Portrait Uffizi / photo by Jan, 2018 |

One of the chief pleasures of the exhibit is the many examples of the art that inspired the Pre-Raphaelites.

Early European Art

|

| Jan van Eyck, 1390-1441 The Annunciation, c. 1436 National Gallery, Washington D.C. / Photo by Jan, 2018 |

Jan van Eyck was the greatest painter of his era in Northern Europe, and his version of the archangel announcing to Mary her upcoming pregnancy is widely revered. My photo has a distracting reflection right in the center, but you can see that every detail is richly imagined. Notice also that the figures are elongated and the space is compressed; this is why art historian of the time considered this to be 'primitive' art.

|

| Master of the Saint Lucy Legend, active c. 1475-1505 Virgin and Child Enthroned with Angels, 1400-1500 FAMSF / Photo by Jan, 2018 |

The art that first interested the Pre-Raphaelites was so old that the artists could not always be identified. This painting is in the same style of another famous painting of the period, known as The Legend of St. Lucy, but the name of the artist is unknown. Here again, every detail is crisp, but the figures are elongated and the proportions are wrong; for instance, if the Virgin were to stand up, her head would bump the top of her throne.

Early Italian Art

The best known Italian artist before Raphael was probably Sandro Botticelli, and the exhibit offers some examples of his work; however, the paintings they show are not the ones that most influenced the Pre-Raphaelites. Botticelli's most important works are very large and never leave the Uffizi Museum in Florence. I'm going to bring in prints from the Internet to give you a better idea of what the Pre-Raphaelites liked.

|

| Sandro Botticelli, 1445-1510 Primavera, c. 1480 Internet grab from Uffizi |

In this dreamy painting, Botticelli united the imagery of Christianity (the Virgin in the center, and the putti overhead) with the imagery of classical mythology (the three graces on the left), and other standard mythological figures in painting, such as Flora (the flower clad maiden on the right).

Venus was the Goddess of Love, who arose fully formed from the sea. To her left the Wind Gods blow her ashore, and separate the strands of her luxuriant hair. On the right Flora welcomes her with a flowing robe. The edges are crisp, the forms are graceful, and details are evenly lighted throughout.

The exhibit did have one excellent example by Botticelli, but I accidentally failed to photograph it, so I'm including an internet grab; it also belongs to the Uffizi, but there are similar versions in two other museums.

|

| Sandro Botticelli, 1445-1510 Madonna of the Magnificat, 1481 Internet grab from Uffizi |

Here we see the complex but balanced composition that Pre-Raphaelites admired, plus the crisp edges, the rich details, the graceful forms, and the rich coloration.

|

| Sandro Botticelli, 1444-1510 Madonna and Child with Two Angels, c. 1470 Naples / Photo by Jan, 2018 |

This is a fairly conventional portrait of the Madonna, with rather dull coloration. The was not the kind of thing that inspired the Pre-haphaelites, but it does have graceful forms and a mystical mood.

|

| Sandro Botticelli, 1444-1510 Idealized Portrait of a Lady (Portrait of Simonetta Vespucci as Nymph), c. 1475 Städel Museum, Franfurt |

This type of idealized portrait, with its mystifyingly complicated hair arrangement, had a great deal of impact of the Pre-Raphaelites, some of whom specialized in idealized portraits.

One of the artists with a strong influence on the Renaissance was Domenico Ghirlandaio, a contemporary of Botticelli. Many artists got their training in his studio, including Michelangelo.

|

| Domenico Ghirlandaio, 1449-1494 Portrait of a Man, c. 1490 Huntington Library / Photo by Jan, 2018 |

|

| Domenico Ghirlandaio, 1449-1494 Portrait of a Woman, c. 1490 Huntington Library / Photo by Jan, 2018 |

Piero di Cosimo was admired by the Pre-Raphaelites for his carefully articulated, naturalistic details.

|

| Piero di Cosimo, 1462-1521 Madonna and Child with the Infant Saint John the Baptist, c. 1510 Liechtenstein, the Princely Collection / Photo by Jan, 2018 |

The image of the Madonna resting on a stump in the wilderness, with a cloth strung from a tree to provide a little shade, is amusingly unassuming. The Christ child waves in a friendly fashion to his cousin, John, who later became known as the Baptist. The Madonna studies a book, presumably some holy work; perhaps she reads aloud to the two children, who are more interested in each other. The composition is balanced and the coloration is rich and jewel-like.

This is the style of portraiture that dominated Northern Europe in the early history of art. It is solemn, but bright and richly detailed.

|

| Lucas Cranach the Younger, 1515-1586 Portrait of a Man, 1545 FAMSF / Jan's photo |

Ironically, as the so-called Pre-Raphaelites matured, they became interested in the artists of the late Renaissance, and even the Venetians, whose robust and sensual figures, dynamic compositions, and deep shadows are a far cry from the work of Piero di Cosimo, or even Botticelli.

|

| Paolo Veronese, 1528-1588 Lucrezia, c. 1580 Kunsthistoriches, Vienna / Photo by Jan, 2018 |

Lucrezia was a heroine of Roman legend, who was an exemplar of honor and courage because she killed herself after she was raped. The Pre-Rapaelites liked the rich coloration of the Venetians and the idea of using a female figure to represent virtue.

The Founders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

William Holman Hunt was a versatile artist who pursued various aspects of Pre-Raphaelite aesthetics over the course of a long career.

|

| William Holman Hunt, 1827-1910 Valentine Reproaching Proteus for His Falsity, 1851 The Makins Collection / Photo by Jan, 2018 |

As part of a movement that was both literary and artistic, the PRB was initially devoted to illustrating medieval legends. This legend of Valentine as a medieval knight is not known to me, but the story is pretty clear: Valentine is in the center with the wronged damsel in a flowered apron kneeling on the ground, and Proteus on the right, also kneeling and hanging his head. The figure on the left is probably the knight's servant.

|

| William Holman Hunt, 1827-1910 The Hireling Shepherd, c. 1853 The Makins Collection / Photo by Jan, 2018 |

This painting from two years later has a simple, beautifully balanced composition (with cultivation on the right and herding on the left), jewel-like tones, crisp details even the the distance, and an instantly readable narrative.

|

| William Holman Hunt, 1827-1910 Henry Wentworth Monk, 1858 National Gallery, Ottawa / Jan's photo, 2018 |

This is a portrait of a Canadian mystic that Hunt met in Jerusalem. He is represented as a modern version of an Early European portrait, such as the example by Lucas Cranach the Younger, above. Notice that the mystic holds a rolled up copy of the London times, as well as a holy book.

|

| William Holman Hunt, 1827-1910 Isabella and the Pot of Basil, 1867 Private Collection / Jan's photo, 2018 |

Reflecting his devotion to poetry, Hunt here depicts a scene from a poem by John Keats, an English romantic poet of the previous generation. Isabella is mooning over this pot of basil because it contains the severed head of her murdered lover, a rather creepy idea to moderns. Hunt elaborated the idea by placing the pot on a richly inlaid altar topped by a gold brocade cloth. A pearlescent water pitcher sits below. Notice that far from being prim and formal, Isabella is a voluptuous figure, in a semi-transparent nightgown, much more like the heroines of Venetian painting.

|

| William Holman Hunt, 1827-1910 Bianca, 1869 Worthing Museum / Jan's photo, 2018 |

Here Hunt goes for a full-blown tribute to the Venetian portraits of idealized women, abandoning complex composition and obscure stories. Bianca was a character in a play by Shakespeare, but who cares? She is the perfect modern realization of a Venetian ideal of beauty.

|

| William Holman Hunt, 1827-1910 The Lady of Shalott, 1890s Wadsworth Atheneum / Jan's photo, 2018 |

Dante Gabriel Rossetti came from a literary family. His father was a Dante scholar, his sister Christina became a famous poet, and his brother William Michael was a member of the PRB who became an influential art critic. Dante Rossetti also established himself in the history of English poetry, but he chose painting as his profession because he thought it would make more money. He became quite successful as a painter, made a lot of money, and continued to write poetry as a pastime. Sometimes he wrote a poem to accompany a painting; sometimes he painted a picture to illustrate a poem.

Although Rossetti painted a variety of literary and medieval subjects, he had a complicated love life, and he became increasingly obsessed with painting a certain ideal type of woman—voluptuous but melancholy, dreamy and decadent. He used a variety of models as his muses, but he gave them all a similar look and attitude. Each of these women is supposed to represent a character in a certain literary work, but that's just an excuse; you don't really need to know the story to get the point.

|

| Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1828-1882 Monna Vanna, 1866 Tate, London / Jan's photo, 2018 |

|

| Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1828-1882 Lady Lilith, 1868 Delaware / Jan's photo, 2018 |

|

| Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1828-1882 Veronica Veronese, 1872 Delaware / Jan's photo, 2018 |

John Everett Millais became the most prominent exponent of the PRB agenda, even though he moved toward greater realism in less than a decade. He was criticized for abandoning his principles, but his later paintings were very popular, and he became one of the wealthiest artists of his day.

|

| John Everett Millais, 1829-1896 Mariana, 1851 Tate London / Photo by Jan, 2018 |

This painting from early in his career (he was 22) is the perfect embodiment of the Pre-Raphaelite aesthetic, using a jewel-tone palette and depicting a scene from a literary source. Mariana started as a character from Shakespeare's play Measure for Measure. Alfred, Lord Tennyson then wrote a poem about her. It seems she has been abandoned by her fiancé for lack of a dowry, and she is passing the time by making a tapestry at table near a window. When she stands to stretch her back, she is supposed to be saying, "My life is dreary—He cometh not!"

|

| John Everett Millais, 1829-1896 The Ransom, 1862 Getty / Photo by Jan, 2018 |

The story in this painting is marvelously clear and its source is clearly literary. The knight in shining armor is ready to give precious jewels to the brigand on the right, for the return of two young girls, presumably his daughters. On the left side of the picture, a page or footman has the ransom note, and a fur rug to cover the girls for the carriage ride home. Between the knight and the brigand is a friend or supporter of the knight who has a bag of gold at hand.

|

| John Everett Millais, 1829-1896 Leisure Hours, 1864 Getty / Jan's photo, 2018 |

Here again are two young girls, but this is a straight-forward portrait commission, with no narrative or medieval elements. It's possible there is some symbolism in the fishbowl, which seems out of place.

|

| John Everett Millais, 1829-1896 Christ in the House of His Parents, c. 1866 Private collection / Jan's photo, 2018 |

The humble, naturalistic detail of this painting is appealing to the modern eye: the way Millais has imagined Joseph's workshop, with tools hanging on the wall, lumber stacked out back, and shavings littering the floor is charming. Joseph has two young helpers (possibly Jesus' siblings), and it looks like Mary's mother Anne is also helping, or perhaps just looking on. Jesus has been trying to help assemble the door, but he has driven a nail into his hand. Mary is comforting him with a kiss, as mothers do. Millais' interpretation of this situation in the New Testament was considered blasphemous by many of his' contemporaries because the characters looked too ordinary and familiar. The controversy made the painting very famous, but was divisive to the Pre-Raphaelites. I was struck by the herd of white cattle and sheep looking on with concern.

The Second Generation of Pre-Raphaelites

The second generation of Pre-Raphaelites includes John Roddam Spencer Stanhope, Edward Burne-Jones, and Burne-Jones' friend, the designer William Morris.

John Roddam Spencer Stanhope painted two of the most remarkable paintings in the exhibition.

|

| John Roddam Spencer Stanhope, 1829-1908 Robins of Modern Times, c. 1860 Private collection / Jan's photo, 2018 |

This painting is so unusual it is nearly surreal. The central section is a dark blob, forcing your eyes around the perimeter. The landscape and rocks are exceptionally naturalistic. But why is this girl on the ground? Did she fall to the ground and drop her apples? Was she cavorting about the countryside wearing a floral wreath and paused for a nap or a daydream? There is a robin with a red breast in the lower right, who seems about to put a leaf on her; a dull-colored robin can barely be distinguished on the left, also taking a leaf her way. The title adds to the puzzlement—the painting is not really about robins, is it?

|

| John Roddam Spencer Stanhope, 1829-1908 Love and the Maiden, 1877 FAMSF / Jan's photo, 2018 |

This painting is a perfect re-interpretation of Botticelli's aesthetic, as shown in Primavera and The Birth of Venus. The composition is balanced, the figures are graceful, the theme is mythical and romantic, every detail is carefully defined. Perhaps the most remarkable aspect is that Stanhope was able to use oil paint to imitate the effect of fresco and egg-tempera painting, techniques that Botticelli used himself.

Edward Burne-Jones was both an artist and a designer. He was a protege of Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

|

| Edward Burne-Jones, 1833-1898 The Heart of the Rose, 1889 Agnew's / Jan's photo, 2018 |

This painting seems very unpleasant to me because of the dark coloration and the way the green of the woman's dress blends into the bush. The story comes from a poem by Chaucer written in the Middle Ages. The black-robed figure on the left is supposed to be a pilgrim; the black-winged figure on the right represents Love, who has led him to the Rose, personified as a woman in a rose bush. That is too obscure for me.

Burne-Jones designed some beautiful tapestries that are part of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco's excellent textile collection, one for Pomona and one for Flora. These are stock figures for decorative tapestries, with Pomona representing fruit and orchards and Flora representing flowers and springtime.

|

| Edward Burne-Jones, 1833-1898 Pomona, 1886 FAMSF / Jan's photo, 2018 |

|

| Edward Burne-Jones, 1833-1898 Flora, 1886 FAMSF / Jan's photo, 2018 |

William Morris was a textile designer who was closely associated with Edward Burne-Jones and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. In 1861, these three artists and several others formed a decorative arts firm, which eventually became known as Morris & Co. This company manufactured and sold the tapestries designed by Burne-Jones. Below are two examples of tapestries designed by Morris himself. You may recognize these bold, repetitive patterns. This company still sells coveted wallpapers and fabrics.

Third Generation Pre-Raphaelites

Among the third generation of artists to become Pre-Raphaelites were three women: Marie Spartali Stillman, Evelyn De Morgan, and Kate Bunce. Although they came late to the movement, they showed particular affinity for its romantic and decorative aspects.

Marie Spartali Stillman first became known for her stunning good looks. She was the daughter of a wealthy Greek merchant based in London, and her Grecian features gave her an exotic look to the pale British; in addition, she was over six feet tall. She was well-known among the Pre-Raphaelites, who vied to use her as a model. But after her marriage to an American journalist, she became one of the most prolific and successful artists of the movement, though she lived in both Europe and the U.S. and raised six children.

This painting creates the mood of romantic melancholy sought after by Pre-Raphaelites. The woman has just received a message carried by a white bird; she keeps corn kernels on her sill for it. She has been sitting by the window to work on a tapestry. The river comes right up to the window; does she live on an island? The river is a way of pointing into the distance, where her love lies. Stillman heightened the romance by softening the edges of her figures, and using fewer fussy details than the original Pre-Raphaelites.

Evelyn De Morgan was the niece and student of John Roddam Spencer Stanhope. She is considered a follower of Dante Gabrielle Rossetti, but instead of dark and sickly images of the ideal woman, her women are fair-haired, robust, and paying attention.

|

| Evelyn De Morgan, 1850-1919 Flora, 1894 De Morgan Collection / Jan's photo, 2018 |

De Morgan's version of the stock figure of Flora, goddess of flowers, is closely related to the style of Botticelli, one of her favorite old masters. The figure's dress and stance are closely related to his Primavera, while her flowing hair recalls The Birth of Venus.

Kate Bunce was not directly connected with the Pre-Raphaelite set, which was mostly based in London. She was born and educated in Birmingham, an industrial town about halfway between London and Liverpool that had its own art academy, and even its own style. Although she did exhibit in London and all over England, as well as Birmingham, and had a successful career, she didn't achieve as wide recognition as the Londoners did. Also the Pre-Raphelite style seemed increasingly quaint in 20th century.

|

| Kate Bunce, 1856-1927 Saint Cecilia, c. 1901 Private Collection / Jan's photo, 2018 |

The gorgeous robe—silken and golden—the gold leaf halo, the crisp edges and abundant detail are all expressive of Pre-Raphaelite aesthetics. Even the space is compressed vertically, like a painting by van Eyck. The head, however, looks very English, and the face shows concentration and determination, rather than the languid melancholy of the typical Pre-Raphelite idealized woman.

The Pre-Raphaelite school was essentially reactionary. They objected not only to conventional British painting but to modern life in general. They dreamed of an imaginary time when beauty reined supreme. But all those lonely ladies languishing in luxurious environments seem really irrelevant and quaint from the 21st century. The Pre-Raphaelites created some romantic effects in their work and it's fun to imagine the medieval world of knights and religion, but you can see why the French dominated art history in the 19th century. The French were looking outside the studio toward the real world, trying to capture the modern look, studying the effect of light and the nature of vision, and they embraced modernity, eagerly painting the newly built urban squares, railways, and bridges.

Monday, August 13, 2018

Clock Dance

Willa Drake—the protagonist of Anne Tyler's latest novel, Clock Dance—is a self-defeating, self-effacing wimp.

Tyler divided Willa's story into two parts. The first part consists of three situations in which Willa made self-defeating choices, shoot-yourself-in-the-foot type choices.

When she is eleven years old, Willa rejects both her parents in a prolonged pre-teen pout. It's easy to see why she rejects her mother: she's a moody person who sometimes leaves her family to fend for themselves, and then returns pretending that nothing has happened. Willa's anger at her mild-mannered, even-tempered father, is harder to fathom. She seems to deliberately take offense at something he says in an effort to comfort her while her mother is gone. The reader is left to wonder the real reason she gets angry and refuses his love. Is it because he is too passive to confront her mother? Because he goes along with the pretense that everything is fine? Or is it because he doesn't take seriously Willa's effort to fill the gap?

By the time she is 21, Willa is so far gone that when the passenger on one side of her in a jet airplane threatens her life with a gun, she doesn't react in any way. She doesn't scream; she doesn't question the guy about what he wants; she doesn't alert her boyfriend on the other side of her; she doesn't alert the stewardess who comes by. Her will is paralyzed. When she later tells her boyfriend, he is incredulous and discounts her story.

She and her boyfriend, Derek Macintyre, are flying to visit her parents because Derek wants to marry her. Where Willa is weak, Derek is willful and assertive. Willa wants to wait until she has finished college, but he wants to marry in the summer coming up and move to California to start his career. His plans are more important to him than her plans, which he discounts. Toward the end of their week-end visit, he announces their engagement to her parents. Her mother says all the right things: she points out that he isn't looking at Willa's side of things and what Willa would have to give up for him. And she particularly notes that Derek had brushed off Willa's story of being threatened on the airplane, because it shows how he disrespects her. Derek confronts her mother in a way that her father never could, and calmly tells her off. Instead of being strengthened by her mother's support, Willa reacts against it, and against her own best interests, by giving into Derek.

After 20 years of predictable life with Derek—giving up college to raise two sons, being the sort of dependable mom she wishes her mother had been—Willa is suddenly left to her own devices when Derek is killed in an accident caused by his own road rage. She feels helpless and incompetent, which is the way he had always treated her. She begins to wonder about the purpose of life, or simply 'why bother?' She had always wanted to be so reliable that her sons could take her for granted, but now she finds that being taken for granted is not very satisfying. She still longs for someone to take care of her, and to boss her around.

The real story, Part II, starts when Willa is 61 years old, and it opens with a call to another life, an offer she can't refuse. It takes the form of a phone call from someone who mistakenly assumes that Willa is the grandmother of an 8-year-old girl whose mother had been shot in the leg, in her neighborhood in Baltimore. She wants Willa to take care of the girl, Cheryl, while her mother, Denise, is in the hospital. Willa is now married to Peter, who is the same type as Derek, and is living the same arid retirement life in Arizona that she would have had with him. Uprooted from her world in California, Willa feels her life is meaningless and boring. When she hears of a child in need of a grandma, she can't resist the temptation to play the role. Perhaps for the first time in her life, she spontaneously makes a major decision, without consulting Peter, and books her flight to Baltimore. Her bid for independence is somewhat muted by his decision to accompany her, condescendingly assuming she can't handle the flight by herself.

Peter is fairly helpful, or at least non-interfering, but his attention is still on his own world, his business associates and golf buddies. Willa adapts to her role as grandmother, which includes adapting to a colorful cast of characters in the poor but respectable neighborhood where Cheryl and Denise live. She becomes so engrossed in her new life that she barely notices when Peter goes back to his world in Arizona. Meanwhile she is developing self-reliance—learning to drive a strange car around a strange town, learning to make decisions and choices on her own, learning to appreciate 'everyday people,' learning, for the first time, to enjoy the absence of a man to dominate her life. And the reader keeps thinking she ought to go back to her husband. Or should she?

My usual preference is for novels that are intellectually challenging, with a difficult vocabulary and complicated sentences, with big ideas and heavy drama. But sometimes I need a vacation from all that, and then I turn to Anne Tyler. Clock Dance is her 21st novel, and I have read about half of them. Her themes are positive and life-affirming, but her stories don't reek of sentimentality and preachiness because her style is so spare and understated. It's like Quaker wood furniture—functional but not fancy, well-crafted but plain. Tyler is generous with homely detail and engaging minor characters, but she is spare in her depiction of Willa's inner life. By leaving a lot unsaid, she forces the reader to use their imagination.

For me, Anne Tyler is consistently good, but never great. But that's okay. It's like simple home cooking compared to gourmet meals—sometimes that's just what I need.

Tyler divided Willa's story into two parts. The first part consists of three situations in which Willa made self-defeating choices, shoot-yourself-in-the-foot type choices.

When she is eleven years old, Willa rejects both her parents in a prolonged pre-teen pout. It's easy to see why she rejects her mother: she's a moody person who sometimes leaves her family to fend for themselves, and then returns pretending that nothing has happened. Willa's anger at her mild-mannered, even-tempered father, is harder to fathom. She seems to deliberately take offense at something he says in an effort to comfort her while her mother is gone. The reader is left to wonder the real reason she gets angry and refuses his love. Is it because he is too passive to confront her mother? Because he goes along with the pretense that everything is fine? Or is it because he doesn't take seriously Willa's effort to fill the gap?

By the time she is 21, Willa is so far gone that when the passenger on one side of her in a jet airplane threatens her life with a gun, she doesn't react in any way. She doesn't scream; she doesn't question the guy about what he wants; she doesn't alert her boyfriend on the other side of her; she doesn't alert the stewardess who comes by. Her will is paralyzed. When she later tells her boyfriend, he is incredulous and discounts her story.

She and her boyfriend, Derek Macintyre, are flying to visit her parents because Derek wants to marry her. Where Willa is weak, Derek is willful and assertive. Willa wants to wait until she has finished college, but he wants to marry in the summer coming up and move to California to start his career. His plans are more important to him than her plans, which he discounts. Toward the end of their week-end visit, he announces their engagement to her parents. Her mother says all the right things: she points out that he isn't looking at Willa's side of things and what Willa would have to give up for him. And she particularly notes that Derek had brushed off Willa's story of being threatened on the airplane, because it shows how he disrespects her. Derek confronts her mother in a way that her father never could, and calmly tells her off. Instead of being strengthened by her mother's support, Willa reacts against it, and against her own best interests, by giving into Derek.

After 20 years of predictable life with Derek—giving up college to raise two sons, being the sort of dependable mom she wishes her mother had been—Willa is suddenly left to her own devices when Derek is killed in an accident caused by his own road rage. She feels helpless and incompetent, which is the way he had always treated her. She begins to wonder about the purpose of life, or simply 'why bother?' She had always wanted to be so reliable that her sons could take her for granted, but now she finds that being taken for granted is not very satisfying. She still longs for someone to take care of her, and to boss her around.

The real story, Part II, starts when Willa is 61 years old, and it opens with a call to another life, an offer she can't refuse. It takes the form of a phone call from someone who mistakenly assumes that Willa is the grandmother of an 8-year-old girl whose mother had been shot in the leg, in her neighborhood in Baltimore. She wants Willa to take care of the girl, Cheryl, while her mother, Denise, is in the hospital. Willa is now married to Peter, who is the same type as Derek, and is living the same arid retirement life in Arizona that she would have had with him. Uprooted from her world in California, Willa feels her life is meaningless and boring. When she hears of a child in need of a grandma, she can't resist the temptation to play the role. Perhaps for the first time in her life, she spontaneously makes a major decision, without consulting Peter, and books her flight to Baltimore. Her bid for independence is somewhat muted by his decision to accompany her, condescendingly assuming she can't handle the flight by herself.

Peter is fairly helpful, or at least non-interfering, but his attention is still on his own world, his business associates and golf buddies. Willa adapts to her role as grandmother, which includes adapting to a colorful cast of characters in the poor but respectable neighborhood where Cheryl and Denise live. She becomes so engrossed in her new life that she barely notices when Peter goes back to his world in Arizona. Meanwhile she is developing self-reliance—learning to drive a strange car around a strange town, learning to make decisions and choices on her own, learning to appreciate 'everyday people,' learning, for the first time, to enjoy the absence of a man to dominate her life. And the reader keeps thinking she ought to go back to her husband. Or should she?

My usual preference is for novels that are intellectually challenging, with a difficult vocabulary and complicated sentences, with big ideas and heavy drama. But sometimes I need a vacation from all that, and then I turn to Anne Tyler. Clock Dance is her 21st novel, and I have read about half of them. Her themes are positive and life-affirming, but her stories don't reek of sentimentality and preachiness because her style is so spare and understated. It's like Quaker wood furniture—functional but not fancy, well-crafted but plain. Tyler is generous with homely detail and engaging minor characters, but she is spare in her depiction of Willa's inner life. By leaving a lot unsaid, she forces the reader to use their imagination.

For me, Anne Tyler is consistently good, but never great. But that's okay. It's like simple home cooking compared to gourmet meals—sometimes that's just what I need.

|

| Anne Tyler, 2017 |

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)