The subject is the significant and innovative Swiss artist Alberto Giacometti; he is usually known as a sculptor, but he also painted portraits. Instead of a plot, we have the process of painting a portrait, and not just a likeness, but a psychological study. For conflict, we have the conflict in Giacometti's soul between living and dying.

In this portrayal, Giacometti is a nihilist, doubtful of the value of life, doubtful of his talent, doubtful that the portrait can ever be completed. For an artist, nihilism is an untenable point of view. If you say that life is a drag, that you are without talent, and that you have taken on an impossible task, you will become paralyzed, and the artist is shown giving up time after time. And yet, as an artist, Giacometti had this up-welling of creativity that forced him to keep trying.

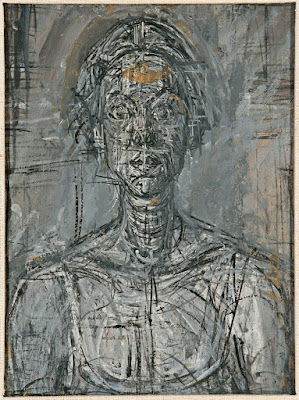

|

| Bust of Annette, 1954 |

For art-lovers who are familiar with Giacometti's attenuated figures in lumpy plaster or his dark, scratchy portraits, Rush's interpretation is pretty convincing. It's easy to believe that the artist was tormented by doubt and negativity. And we accept that periodically he was forced to come up for air to seek fun, color, and wild sex, to express his aliveness.

It's lovely to see a thoughtful work about an artist, in contrast with the usual subjects for movies. But what really interested me was the team that worked on it, especially recognizing that some of them had worked together before. The film was written and directed by Stanley Tucci, who is usually known as a character actor. He has also directed a number of films, including Big Night, which is the one that I've seen. He also co-starred in that movie with Tony Shalhoub, who later became famous as the TV detective Monk. They played brothers in the movie, and Shalhoub reappears in Final Portrait as the brother of Giacometti. It interests me that these buddies took an interest in a story about an artist, enough interest to read the book written by the subject of the portrait, James Lord, and to marshal the resources to convey such a specialized subject to film.

Geoffrey Rush, who plays the lead role, has won an astounding number of acting awards in the U.S., Britain, and his native Australia, frequently for playing tortured geniuses. His craggy face makes him look remarkably like the real Giacometti. His ability to handle a paintbrush convincingly suggests that he looked long and hard at the artist's work. It's curious to note actors taking interest in art; actors working on a subject that is not likely to be a big box-office success. The movie showed in only one theater in our area, one that specializes in artsy movies, the Cinéarts Palo Alto.

Since the release of the movie, Rush has joined the long list of Hollywood types who have been accused of sexual misconduct. He denies the accusation, and his lawyer says he is distraught by the damage done to his reputation and his career. Whatever he may have done seems quite irrelevant to his massive acting talent.

The other actors in the movie all did a good job, but their roles were comparatively small. Sylvie Testud played Giacometti's skinny muse as a mirror of the artist's tortured soul. Clémence Poésy played the whore who tickled his fancy as silly and frivolous and utterly distracting. Arnie Hammer played James Lord, the writer who sat for his portrait; his was the least demanding role, since he was generally trying to sit rigidly and maintain the same neutral expression. On the other hand, sitting for a portrait is difficult work, especially a psychological study, and pretending to sit could be even more vexing. With very few lines to work with, Hammer conveyed the complex mix of fascination and boredom involved in complying with the artist's needs and obsessions.

A character study of an artist will have a limited audience, presumably. But for art-lovers, this is good stuff. It actually makes a positive contribution to understanding Giacometti's meaning and motivation, and it elucidates the compulsive nature of creativity.