The museum has been closed for three years—long, tedious years for fans of modern art—for the $305 million addition. The work is finishing up now, the collection is in place, and preview days are being given to "charter" members, that is members who continued paying dues during the dark period, like myself and Dan. The new museum opens officially May 14.

We were eager to see what the new building was like, of course, but our major excitement was to experience the Fisher collection, and to understand why it is so highly valued.

The Fisher Collection

The Fisher collection is rooted in blue-chip work of the white male art world of 1960s America and Germany. It compliments the museum's regular collection, since it has many of the same artists. For the opening, the Fisher collection is shown intact, so you will encounter the same artists in two different locations. In the future, the museum will be able to show all the works by the same artist in the same galleries. You can appreciate an artist better when you can see many of their works at the same time. The work of several of my favorite artists is presented in great depth.

The examples below—my own iPad photos—are from the Fisher collection, unless otherwise noted.

Wayne Thiebaud, born 1920

California artist, Wayne Thiebaud, is still working at age 96. Whether he is painting sweet treats or steep streets, flat rivers or towering canyons, demure students or frank nudes, Thiebaud makes it all look delicious, if slightly out of reach. Early in his career, he preferred blunt, straight-on compositions, but later he exploited unusual, if not impossible, perspectives.

|

| Wayne Thiebaud, b. 1920 Confections, 1962 SFMOMA's regular collection |

|

| Wayne Thiebaud, b. 1920 Student, 1968 |

|

| Wayne Thiebaud, b. 1920 Girl with a Pink Hat, 1973 |

|

| Wayne Thiebaud, b. 1920 Sunset Streets, 1985 |

|

| Wayne Thiebaud, b. 1920 Flatland River, 1997 |

|

| Wayne Thiebaud, b. 1920 Valley Streets, 2003 |

|

| Wayne Thiebaud, b. 1920 Canyon Mountains, 2012 |

Ellsworth Kelly, 1923-2015

New Yorker Ellsworth Kelly, who just died this past December, was the ultimate minimalist. Minimalism is an approach to art that aims to produce maximum impact with limited means. Kelly confined art to explorations of primary colors and simple geometrical shapes, and the interaction between them. He gave the results importance by making them large and imposing.

The following examples are from a series of multi-panel works from the Fisher collection.

The following examples are from a series of multi-panel works from the Fisher collection.

|

| Ellsworth Kelly, 1923-2015 Red Green, 1968 |

|

| Ellsworth Kelly, 1923-2015 Black Triangle with White, 1976 |

|

| Ellsworth Kelly, 1923-2015 Yellow Relief with Black, 1993 |

|

| Ellsworth Kelly, 1923-2015 Red Curves, 1996 |

|

| Ellsworth Kelly, 1923-2015 Red on Red, 2001 |

|

| Ellsworth Kelly, 1923-2015 Curve XXI, 1978-1980 |

|

| Ellsworth Kelly, 1923-2015 Untitled (Mandorla), 1988 SFMOMA regular collection |

|

| Ellsworth Kelly, 1923-2015 Spectrum Colors Arranged by Chance, 1951-53 SFMOMA regular collection |

|

| Ellsworth Kelly, 1923-2015 Spectrum I, 1953 SFMOMA regular collection |

Gerhard Richter, born 1932

German artist Gerhard Richter has three completely different modes. One is to paint blurry copies of photographs, whether portraits, objects, or scenes. The second is to create intensely contrasting abstractions using various devices to scrape the paint into layers. The third is to experiment with color in a flat, impersonal manner.

|

| Gerhard Richter, b. 1932 Cityscape Madrid, 1968 |

|

| Gerhard Richter, b. 1932 Two Candles, 1982 |

|

| Gerhard Richter, b. 1932 Seascape, 1998 |

|

| Gerhard Richter, b. 1932 The Reader, 1994 SFMOMA regular collection |

|

| Gerhard Richter, b. 1932 Janus, 1983 |

|

| Gerhard Richter, b. 1932 Abstract Painting, 1992 |

Chuck Close, born 1940

|

| Chuck Close, b. 1940 Roy I, 1994 |

|

| Chuck Close, b. 1940 Agnes, 1998 |

|

| Chuck Close, b. 1940 Lorna, 2006 |

Anselm Kiefer, born 1945

German painter Anselm Kiefer is concerned with the history and culture of his country, and dwells on scenes of destruction and loss in wall-size paintings that often incorporate materials such as straw, ash, clay, lead, and shellac. He also does sculptural installations on the same themes.

|

| Anselm Kiefer, b. 1945 Margarethe, 1981 |

|

| Anselm Kiefer, b. 1945 Wayland’s Song, 1982 |

|

| Anselm Kiefer, b. 1945 Sulamith, 1983 |

|

| Anselm Kiefer, b. 1945 Operation Sea Lion, 1983-84 |

|

| Anselm Kiefer, b. 1945 Melancholia, 1991 |

The Big Five

Women in the Fisher Collection

Who was that again? In chronological order.

Wayne Thiebaud is a California artist whose style is realistic with romantic overtones.

New Yorker Ellsworth Kelly was the ultimate minimalist painter.

German artist Gerhard Richter does blurry paintings of photographs, scraped paintings with intense colors, and detached color experiments.

American Chuck Close paints only faces, usually on a very large scale, in a variety of techniques.

German Anselm Kiefer dwells on scenes of destruction using natural materials such as weeds and lead.

Now when you visit SFMOMA, instead of saying, "Huh?" you can say, "Oh sure. I recognize his style."

Wayne Thiebaud is a California artist whose style is realistic with romantic overtones.

New Yorker Ellsworth Kelly was the ultimate minimalist painter.

German artist Gerhard Richter does blurry paintings of photographs, scraped paintings with intense colors, and detached color experiments.

American Chuck Close paints only faces, usually on a very large scale, in a variety of techniques.

German Anselm Kiefer dwells on scenes of destruction using natural materials such as weeds and lead.

Now when you visit SFMOMA, instead of saying, "Huh?" you can say, "Oh sure. I recognize his style."

Women in the Fisher Collection

|

| Agnes Martin, 1912-2004 Night Sea, 1963 |

|

| Agnes Martin, 1912-2004 Drift of Summer, 1965 |

|

| Agnes Martin, 1912-2004 Untitled #9, 1995 |

|

| Joan Mitchell, 1925-1992 Harm’s Way, 1987 |

|

| Lee Krasner, 1908-1984 Polar Stampede, 1960 |

|

| Pat Steir, b. 1938 Three Pointed Waterfall, 1990 |

Women Artists in the Collection of SFMOMA

Fortunately, SFMOMA's regular collection includes paintings by several other women.

Possibly the greatest portrait painter of the 20th century was Alice Neel. Although Chuck Close depicted faces, he didn't do character studies, in the tradition of Rembrandt, for instance. Neil's portraits are notable for their expressionistic use of line and color and their insight into character.

|

| Alice Neel, 1900-1984 Geoffrey Hendricks and Brian, 1978 |

|

| Dorothea Tanning, 1910-2012 Self-Portrait, 1944 |

|

| Jay DeFeo, 1929-1989 The Verónica, 1957 |

|

| Joan Brown, 1938-1990 After the Alcatraz Swim 1, (1975) |

|

| Vija Celmins, b. 1938 Night Sky #16, 2001 |

|

| Hung Liu, b. 1948 The Botanist, 2013 |

|

| Dana Schutz, b. 1976 Ear on Fire, 2012 |

Modern and Contemporary Sculpture

The Fisher collection also includes several masterpieces of 20th-century sculpture. Combined with SFMOMA's regular collection, the museum is now able to show a fairly complete survey of sculpture in that century. The following examples come from both collections, as noted.

Sculptors adopted abstraction more readily than painters. It seemed natural to create whole new forms instead of laboring to imitate reality.

Women sculptors of the 20th century were so bold and ingenious that the art world was less concerned with their gender than in painting.

The first important abstract sculptor was Englishman Henry Moore. In the first half of the century his works dominated the museum landscape.

|

| Henry Moore, 1898-1986 Working Model for ‘Oval with Points,’ 1969 Fisher Collection |

|

| Barbara Hepworh, 1903-1975 Sphere with Inner Form, 1963 Fisher Collection |

|

| Isamu Noguchi, 1904-1988 Shodo Flowing, 1959 Fisher Collection |

|

| Isamu Noguchi, 1904-1988 Cronos, 1947-1964 SFMOMA Collection |

|

| Isamu Noguchi, 1904-1988 Samothrace, 1984 Fisher Collection |

|

| Beverly Pepper, b. 1924 Tarquinia Cone Column, 1981 Fisher Collection |

|

| Ruth Asawa, 1926-2013 Untitled (S.046abcd), c. 1960 Collection of SFMOMA |

|

| Ruth Asawa, 1926-2013 Untitled (S.114, Hanging, Six-Lobed Continuous Form with a Form), c. 1960 Collection of SFMOMA |

Dan Flavin, an American sculptor, added two radical ideas to minimalist sculpture. By working exclusively with regular fluorescent bulbs, he introduced the idea of using standardized industrial units as well as using light to create form.

|

| Dan Flavin, 1933-1996 the diagonal of May 25, 1963 Collection of SFMOMA |

|

| Dan Flavin, 1933-1996 “monument” for V. Tatlin, 1969 Fisher Collection |

|

| Dan Flavin, 1933-1996 untitled (to Barnett Newman) two, 1971 Collection of SFMOMA |

|

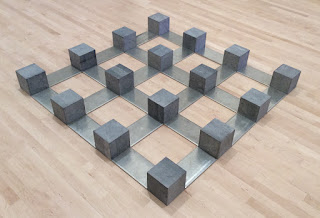

| Carl Andre, b. 1935 Copper-Zinc Plain, 1969 Fisher Collection |

|

| Carl Andre, b. 1935 Belgica Blue Tin Raster, 1990 Fisher Collection |

|

| Carl Andre, b. 1935 13th PbFe Triangle, 1987 Fisher Collection |

|

| Carl Andre, b. 1935 9th Cedar Corner, 2007 Fisher Collection |

|

| Carl Andre, b. 1935 Furrow, 1981 Fisher Collection |

Balance was also a major interest of American sculptor Richard Serra. Early in his career he produced exercises in balancing heavy materials, without apparent concern for aesthetic effect. This is a type of Minimalism.

|

| Richard Serra, b. 1938 Floor Pole Prop, 1969 Fisher Collection |

|

| Richard Serra, b. 1938 House of Cards, 1969/1978 Fisher Collection |

|

| Richard Serra, b. 1938 1-1-1-1, 1969/1986 Fisher Collection |

Another artist who plays with balance is American sculptor Joel Shapiro. He composes forms out of rigid beams, but somehow they playfully evoke the humanoid.

|

| Joel Shapiro, b. 1941 Untitled, 1989 Collection of SFMOMA |

|

| Richard Long, born 1945 Autumn Circle, 1990 Fisher Collection |

The only work by a black artist that was shown in the opening exhibit of the Fisher Collection was a sculpture by Martin Puryear. However, SFMOMA has a long-standing commitment to Puryear, so they complemented the Fisher piece with two from their regular collection. The unique element about his style is his concern for hand craftsmanship Notice that these works are from the 21st century.

|

| Martin Puryear, b. 1941 Two Plus Seven, 2004 Collection of SFMOMA |

|

| Martin Puryear, b. 1941 Title unrecorded Collection of SFMOMA |

|

| Martin Puryear, b. 1941 Malediction, 2007 Fisher Collection |

But where are all the people? Some sculptors stubbornly pursued the figure in the 20th century despite the dominant trend toward abstraction, but instead of carving or modeling free-hand, they tended to use some complicated technique to apply a mold directly to the subject. George Segal deliberately left his figures crude and artificial, while giving them 'real' settings.

By contrast, Duane Hanson finished his figures with such detail that museum visitors sometimes assume they are real people, and stroll right by them. This model for the next example was the artist's own son.

|

| Duane Hanson, 1925-1996 Policeman, 1994 Fisher Collection |

|

| Duane Hanson, 1925-1996 Policeman, 1994 Fisher Collection |

|

| Charles Ray, b. 1953 Sleeping woman, 2012 Collection of SFMOMA |

|

| Charles Ray, b. 1953 Sleeping woman, 2012 Collection of SFMOMA |

English sculptor Marc Quinn is interested in the contemporary practice of people creating their own look and using their skin as a canvas for a personal statement. This example is molded from concrete.

|

| Marc Quinn, b. 1964 Zombie Boy (City), 2011 Collection of SFMOMA |

|

| Marc Quinn, b. 1964 Zombie Boy (City), 2011 (detail) Collection of SFMOMA |

Another British sculptor, Antony Gormley, used metal bars to create a human figure that expresses the way sub-atomic particles and energy that make up our bodies is integrated with those that compose the universe around us.

|

| Antony Gormley, b. 1950 Quantum Cloud VIII, 1999 Fisher Collection |

Another group of sculptors re-created or re-used real objects with some sort of symbolic distortion. Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen generally recreated common objects on a massive scale.

|

| Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen Inverted Collar and Tie — Third Version, 1993 Fisher Collection |

|

| Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen Geometric Apple Core, 1991 Fisher Collection |

|

| Sherrie Levine, b. 1947 Fountain, After Marcel Duchamp, 1991 Collection of SFMOMA |

|

| Jeff Koons, b. 1955 Large Vase of Flowers, 1991 Collection of SFMOMA |

|

| Ai Weiwei, b. 1957 Colored Vases, 2007 Collection of SFMOMA |

The New Building

The new wing of SFMOMA— essentially a whole new building—works quite well, especially considering the architectural challenges. The Norwegian architecture firm Snohetta crammed a huge structure that triples the museum's exhibition area into a long, improbably-shaped space that didn't even seem to exist before they started. The galleries have abundant, even light and a layout that is fairly easy to figure out. Wide halls and gathering places will facilitate the flow of crowds when it opens May 14.

Aesthetically, the new structure is a little disappointing. The exterior is an off-white cloak of fiberglass-reinforced polymer panels that are rippled to suggest the waves in the bay, or perhaps a layer of fog. It sticks out like a sore thumb above the classy original building by Mario Botta. This awkward choice is justified by the fact that stone or brick cladding would have made the building too heavy. It is also noteworthy that artificial cladding with an arbitrary pattern seems to be part of a contemporary pattern, as the new Broad Museum in Los Angeles has a similar facing with a net-like pattern.

The interior is a good example of Minimalism. The galleries do nothing to call attention to themselves. The flooring is bland, compared to the rich black stonework in the Botta building, and the woodwork is pale birch, compared to the warm teak-colored woodwork in the original building. These decisions were probably economic, but they also create a very modest, disappearing sort of atmosphere. The aesthetic touches are exterior balconies for sculpture and views, long hallways with well-placed stairways, and plenty of windows to connect the museum with the city.

The expanded SFMOMA, with its spacious new building and its impressive new Fisher Collection, is a great asset to the city and is bound to be a major tourist draw.

Aesthetically, the new structure is a little disappointing. The exterior is an off-white cloak of fiberglass-reinforced polymer panels that are rippled to suggest the waves in the bay, or perhaps a layer of fog. It sticks out like a sore thumb above the classy original building by Mario Botta. This awkward choice is justified by the fact that stone or brick cladding would have made the building too heavy. It is also noteworthy that artificial cladding with an arbitrary pattern seems to be part of a contemporary pattern, as the new Broad Museum in Los Angeles has a similar facing with a net-like pattern.

The interior is a good example of Minimalism. The galleries do nothing to call attention to themselves. The flooring is bland, compared to the rich black stonework in the Botta building, and the woodwork is pale birch, compared to the warm teak-colored woodwork in the original building. These decisions were probably economic, but they also create a very modest, disappearing sort of atmosphere. The aesthetic touches are exterior balconies for sculpture and views, long hallways with well-placed stairways, and plenty of windows to connect the museum with the city.

The expanded SFMOMA, with its spacious new building and its impressive new Fisher Collection, is a great asset to the city and is bound to be a major tourist draw.